| |

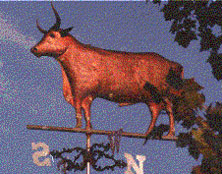

THE "T 4 1" STEER

The T 4 1 Steer weather vane was designed for and purchased by Robert A. "Bob Houston and placed on his mansion in the 1880's. (I would guess in the first half of that decade as big drives from this area ended about 1887.)

The idea is said to have originated while on cattle drives through the Kansas area where Houston observed weather vanes in the shape of barnyard animals. Houston decided that he wanted a weather vane of a steer of a proportionate size for the mansion that was then under construction. Kansas City could not provide the facilities to make such a large vane and it was finally completed in New York City. The vane is gold leaf over copper and is 3 1/2 feet tall and 4 1/2 feet long. It weighs 130 pounds.

The steer was shipped to Gonzales in pieces and assembled by a tinner named F.C. Franks and mounted on a turret on the new mansion just as the house was completed. The T 4 1 brand had been omitted when the steer was being crafted and Franks took punch and a maul and placed the brand on the steer after it was assembled. Perhaps this could be listed as one of the more unusual "brandings" of the period. The vane remained on the Houston home for a number of years after Houston's death.

The family sold the home and it became the Arlington Hotel. Around 1910-15 (date not positive) the steer was given to John D. DuBose an old friend of the family by HoustonÕs son, and it was placed on the Randle-Rather Building. Sometime after that (1925-30 ???) the steer was given to city marshal N.D. Cone by DuBose. At this point the story gets even more cloudy as one story says the steer was given to the city of Gonzales and one says it was leased to the city for 1 dollar for 99 years. At any rate, the steer was placed on the city municipal building for a time. When the fire station was remodeled, the steer was restored and placed on the cupola .

Life On The Trail

by Murray Montgomery

The cowboy legacy is very much alive in Texas and it has been that way for a long time. After the Civil War, times were tough in Texas and throughout the South. Men returning from that devastating conflict found it hard to make a living. Texas, it seemed, was short on everything; everything that is, but cattle. It has been said that the Texas trail drivers literally saved this State from financial disaster in those years following the Civil War. The Gonzales Inquirer reported that the vast herds of cattle in this area alone brought in well over a million dollars between the years 1867-1895.

The Hollywood movies have always glamorized life on the trail and would have folks believe that every cowboy was totin' a gun. Fact is, the work was anything but glamorous. According to The Handbook of Texas: Most days were uneventful; a plodding, leisurely pace of ten to fifteen miles a day allowed cattle to graze their way to market in about six weeks. And many trail bosses would not allow their men to carry pistols for fear that the weapon would discharge accidentally, or otherwise, and cause a stampede. Day-to-day boredom on the trail was occasionally interrupted by stampedes, dangerous river crossings, and violent weather. But an encounter with hostile Indians was a rare occurrence. The ordinary cowboy made from $25 to $40 a month.Horse wranglers would get about $50 or more. The cooks and ramrods would earn about $75 monthly while the trail boss would take in around $100. Some outfits even had a sort of profit sharing program for the trail bosses. It must have been a hard way to make a living.

The cowboy was in the saddle from dawn till dusk, never knowing what he might have to face before the day was over. If he got on the bad side of the trail boss, he might spend the day riding drag at the rear of the herd and eating dust all along the way. Men driving the chuck and equipment wagons fared much better. They led the herd and were always on the look out for suitable campsites. And on the brighter side, they didn't have to eat as much dust as that poor old boy riding drag. Much has been written over the years about the Texas cowboy. And in 1923, The Gonzales Inquirer put out a special edition celebrating the paper's 70th anniversary.

In that edition they included an Old Trail Drivers section honoring those men who drove cattle up the trail from Gonzales County. During a reunion of the Texas Trail Drivers Association, held in Gonzales in 1923, more light was shed on the life of the cowboy. Mr. George B. Saunders, president of the TTDA, spoke at the meeting. He said the average person did not conceive of the volume of business done through the work of the old trail drivers. He claimed that the trail drivers deserved the most credit for the development of Texas after the Civil War. Another speaker at the meeting, J.B. Wells, gave his account of life on the trail. Wells said he had driven cattle in years when practically every stream was dry. And other years when every stream was flowing with so much water that the men had to swim across with the cattle.

Wells described another exciting event on a drive through Indian country: One day a band of Indians swooped down on us and rode around the edge of the herd, shouting, in an effort to stampede our cattle. Mr. Wells was quick to point out that they offered the Indians all their supplies to take the savages' minds off their cattle. We very generously turned over to them all the beans, bacon, coffee, sugar and other eatables we had, he said. They were left in uninhabited country without food for several days until they reached a place where they could buy supplies. They had no money and had to trade cattle for provisions. On one of his drives, J.B. Wells spoke of seeing a man named Hardin kill three men in a drunken brawl on the trail. He didn't give the mans first name, so one can only speculate as to if it was John Wesley who did the killing.

One old cowboy, L.D. Taylor, gave an account of his adventures on the trail. He spoke of being in the saddle for 24 hours without food or sleep. Taylor told of trying to hold the herd in check during blinding thunder and hail storms. You never knew when you would be run over and killed, he said. But despite the pain and hardships, the trail drivers continued to send large numbers of cattle up the trail to the northern markets. According to The Gonzales Inquirer, the following herds were driven from Gonzales County in 1878. G.W. Littlefield, 6,000 head; Littlefield and J.D. Houston, 8,000; Lewis & Dilworth and R.A. Houston, 4,000; Lewis & Dilworth and Parramore, 2,500; Lee Kokernot, 2,000; Jesse McCoy and R.H. Floyd, 2,500. At the time these herds went up the trail, prices for cattle varied from six to fifteen dollars per head. That was big money back then and it was those dollars that put Texas back on solid financial ground.

The old trail drivers drove their last herds and secured a place in history years ago. But the tradition of the cowboy way of life in Texas, will live forever. Hodges Family The Hodges family lived at Pecan Branch, a few miles west of Gonzales. There was a church for worship and a school for the children to attend. During these years the Chisholm Trail developed. Cattle from Gonzales County and further south were gathered in a large well defined valley below Ducan Hill. In the evening after the herds were settled down, the young drovers would ride over to serenade the pretty Hodges girls. Gertrude, the oldest, remembered the cowboys as they played their guitars and sang, but no conversation with the young men was allowed.

Coop Smith's Poke of Coffee

Uncle Coop was freighting between Indianola and Gonzales. He carried out corn and skins to trade for goods the people in Gonzales needed. Uncle Coop could have been paid in paper money, but trade was better. Currency was not very stable in those days, when the fall of the Alamo was a poignantly fresh memory. On one trip to Indianola, Uncle Coop tied his oxen and joined the group of men loitering in front of the general store. He always gathered his news first and did his trading afterwards.

This time, among other items, he heard that the boat from New Orleans had brought coffee. "You can buy it right here at the store," a thickly bearded farmer announced. "Unless you want a hundred pound sack . That you get down at the docks". Uncle Coop bought a mess of coffee as a special treat for his home folks. He looked at it curiously. The storekeeper said it was coffee, but to all appearances it was only shelled-out green beans! Expensive, too, for such plain-looking beans. But Uncle Coop had a yen and he took a chance; he bought a hundred pound bag. Back in Gonzales,

Uncle Coop's mother, Mrs.Isam Smith, was enthusiastic over the poke of coffee and quickly saw the makings of a party. To the hospitable early Texan it was unthinkable that a treat should not be shared with one's friends. She decided on a quilting bee. By mid morning of the appointed day wagons filled with families had arrived. Those on hand as early as nine o'clock had the privilege of advising with with Mrs.Smith on how to prepare the coffee. There were no recipes, no information whatsoever on how to cook these peculiar looking beans. But, of course, everyone knew that beans had to be boiled. Mrs. Smith had soaked the beans overnight,to make the cooking easier. And into the cast-iron pot hanging on the big open fireplace in the kitchen went the green beans-along with a choice ham. Naturally, everyone agreed ,it was proper to boil them with a ham, like any other kind of bean.

Soon the aroma of boiling ham, mingled with something strangely different, filled the air. Outside, the men helped shuck a neighborly supply of corn, then sat around chewing tobacco and talking about the latest clashes with the Mexicans Gradually, concern and misgivings crept over the gathering. It was whispered that the coffee was turning a bilious green. Soon everybody was in the kitchen, alive with curiosity. Someone suggested parboiling, and the cooking process started all over again. Come one o'clock, two, still the beans weren't done. Guests drifted in, lifted the lid and peered into the pot, then drifted out again, shaking their heads with misgivings. At three oÕclock a meeting was called to decide what to do. It was agreed that something was wrong. The stuff looked queer, tasted peculiar and was absolutely unchewable. This last, to Uncle Coop was the bitterest pill of all. A victim of lockjaw, he had expected to mash his coffee with a fork and push it between his teeth on a knife. It was decided, reluctantly, to throw the stuff out. "Mind where you throw it," Mrs. Smith cautioned. "It might kill the hogs."

|